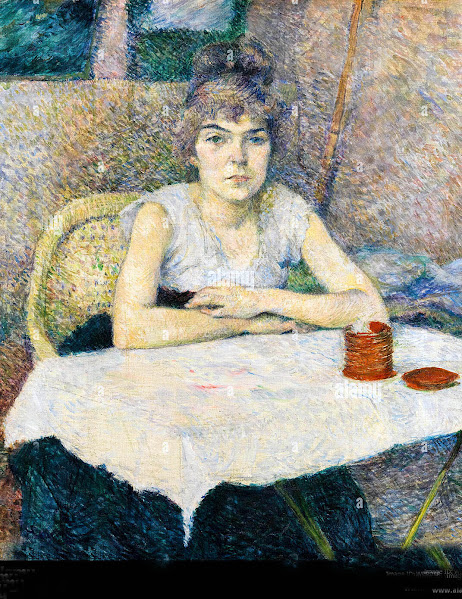

This painting has the strange title of Poudre de Riz (Rice Powder), so named after the chalky mask this woman is forced to wear to attract customers. Though the woman is obviously young, not much more than a girl, there is nothing young about her facial expression, the tough, jaded look that has so much vulnerability and sorrow behind it. No one starts off in life planning to be a prostitute. nor did Henri decide to be a dwarf and an alcoholic. One must make the best of it, mon cheri.

Wednesday, July 30, 2025

Toulouse! Toulouse! Even More Lost in Lautrec

Friday, July 25, 2025

Toulouse-Lautrec: zoom in

Lautrec, Lautrec - I know you too well

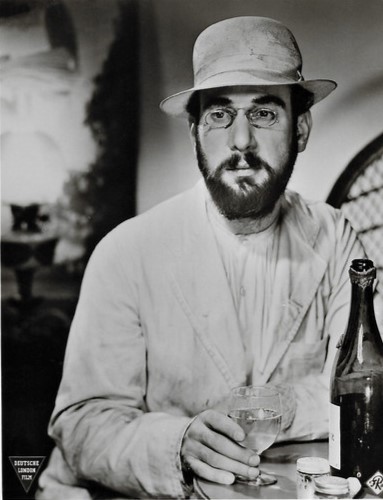

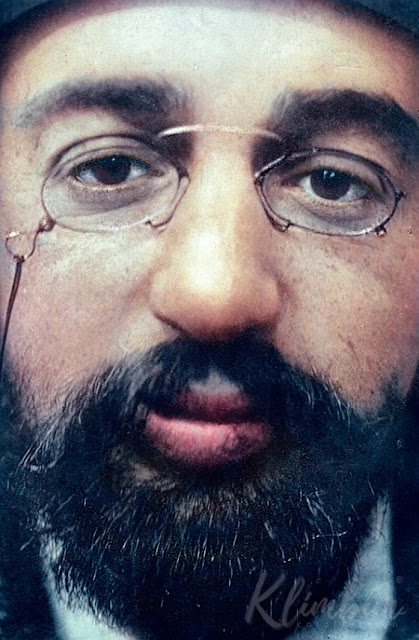

One of my favorite images of Lautrec. Labelled as a "trick photo", I actually think he was magical enough to split himself in two and portray himself. the Two Henris. both spectator and subject.

I love the intent way he studies himself, pencil poised, and the slightly aw-shucks fake modesty of his subject. probably imitating every falsely coy nude model he ever paid to pose. As usual, his face is full of elegance and sly wit, but still, essentially, unreadable.

What's coming across in the Julia Frey bio is his humor, which has been downplayed in favor of the tortured artist in just about every book, movie or bio I've ever seen. Of course he suffered - Frey does say his close friends felt they were helplessly watching as he drank himself to death. unable to do anything to stop him.

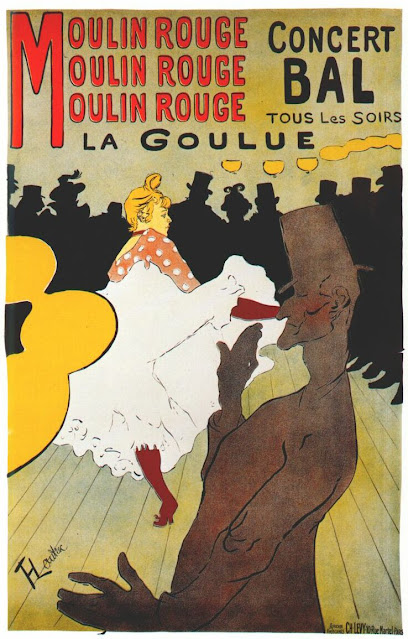

So he WAS two Lautrecs, at least - the wealthy aristocrat, who never needed to work and who only visited those dives as a form of slightly contemptuous recreation, and the almost skinless artist melding into those heartbreaking brothel scenes, becoming one with the cabaret acts (the little man in the corner scribbling on a napkin, which is actualy what he did, not just something in the movie), stripping off the masks, holding up what seems like an actual camera lens to capture the swish of skirts and the bloodthirsty screams of the dancers as they fell violently into a row of splits.

I'm not trying to make this "good", in fact I can barely write it at all, and though I have posted the last few entries on Facebook, I really don't know why. No one reads this blog any more and I know it, so why do I even do it? And I am even more certain that nobody bothers with my Facebook entries, except for the odd one that is utterly trivial. It says more about them than me, and I know it, but it still hurts. Has this all been in vain?

I suppose I do this as a distraction. The writing game has revealed itself to be even more mercenary and heartless than I thought. Everybody's hustling. Everything is for sale. If it's no sale, you don't exist any more, as it is almost entirely a popularity contest, even worse than the living hell I went through in high school.

And I've had enough of that.

But who wants to know? As the song says, the game of life is hard to play - I'm going to lose it anyway. So if writing is communication, I'm not sure I'm communicating at all any more. Henri never needed to worry about selling his work - his magnificent posters were the kind of advertising no other painter had ever known before, and people tore them off doorways and walls, perhaps knowing they had something of real value.

But here he is, Lautrec painting Lautrec, as if nobody else notices him, so he must portray himself.

It could be argued that every painter paints themselves - just look at our old buddy Vincent, and the more modern Frida Kahlo - but few were actually able to photograph themselves doing it. Oh, you want a self-portrait? Well, here I am painting myself! Will I get the details right? No doubt someone will say he does not. The more some people talk, the less they say. But did he give a shit? Yes and no. The bon vivant surface (usually drunk) hid a desperately broken heart which peeps through in some of his photos.

In my Facebook post, I compared Lautrec to Chaplin's Little Tramp. Though no doubt someone will say it's an absurd comparison and that Chaplin knew nothing about Lautrec, I still think it's a worthy insight. (And I'm glad somebody does, because let's face it, nobody else will care enough to find out.)

It was hard for him, not so much to love as to be loved, and as I lay there on the pullout bed in more pain than I thought I would ever experience, I truly believed in my soul that no one had ever cared about me at all. In all my days, I had never once been truly loved, though I had lavished love on everyone around me for decades.

Worse, no one even noticed.

That wounded, devastated child who never should have been born, the late-in-life embarrassment (for they truly did NOT want another baby, and my mother even told me straight-out that she wanted an abortion but her doctor talked her out of it), the disappointment, the one who did not add anything to the family's prestige, who didn't even have a university degree and wrote novels that nobody read - . Oh yes. At the core, we are one.

Wednesday, July 23, 2025

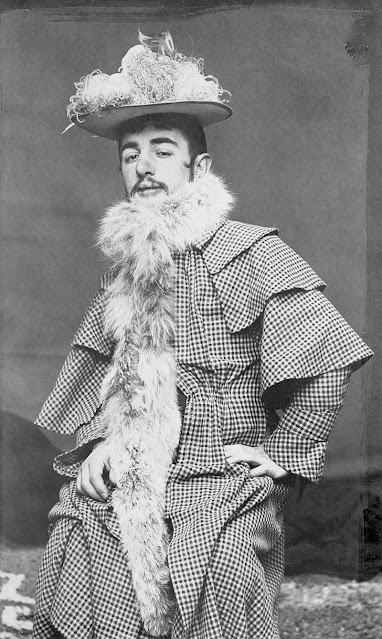

Lost in Lautrec: why Jose Ferrer was the best Toulouse

I watched the movie long before I knew very much about the man. But as with that other painter-of-the-people, Van Gogh, Lautrec's artworks are - what? Just around, everywhere. It's fashionable to hate the Hollywood versions of great artists (Lust for Life, which I really love, is universally loathed among art snobs), but to tell you the truth, I think Ferrer comes closer to becoming Lautrec than any other actor could, or should even try to.

Toulouse, Toulouse! Why do I feel that I know you?

He'd make fun of himself, cut ahead of the line, and get the jabs in before anyone else could take a stab.

.jpg)