OK then, this is NOT going to be an essay.

This is NOT going to be a biography (there are plenty of those).

This won't be a rehash of the Jose Ferrer movie (much as I love it).

So what will it be?

When you begin to creep and sneak into the darkly bright, incandescent, alley-smelling world of Lautrec, you come away changed, if in fact you come away at all.

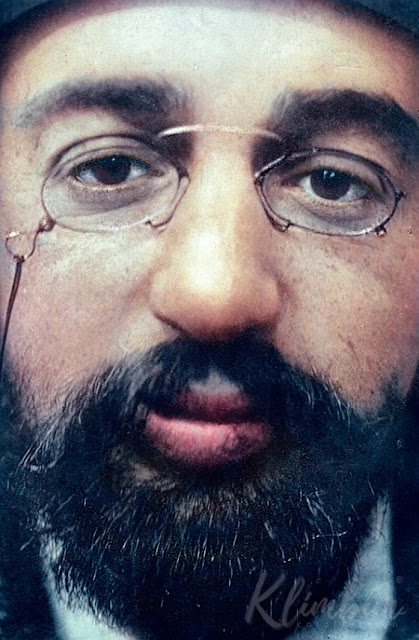

Unknowable, yet, in a sense, too known. Known for his sneaking and creeping nocturnal habits, as much for his famous header down the stairs when he was a child (note: it didn't happen) and his aristocratic inbreeding as for his astonishing genius, the way masterpieces flew out of his tiny warped body, his fiery mind.

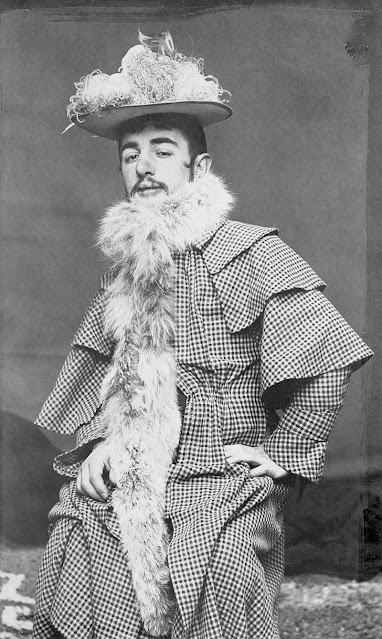

I won't write about all the details of his life, as it was pretty short anyway (oops, Freudian slip! But it's one I think he would enjoy.) He made a kind of spectacle of himself, created a public persona, the inevitable cane, bowler hat and natty suit coat sitting so neatly above the stumpy atrocity of his legs.

I say atrocity, only because of what it did to him to be so disabled, and as a result, no doubt in constant pain. Is it any wonder he frequented those steamy night spots, drowning his diminutive self in gall and bitter wormwood?

(Absinthe-minded, he was, and it finished him off, but oh what glory came before!)

The tumble down the stairs didn't happen, except in the movie, but inbreeding did. It was the embarrassing family secret, first cousins marrying first cousins in a long line of bleeding aristocrats, coming to a screeching dead end with Henri, his legs crumbling away under him, his facial features almost as distorted as King Charles II of Spain, the inbreeding train wreck of all time.

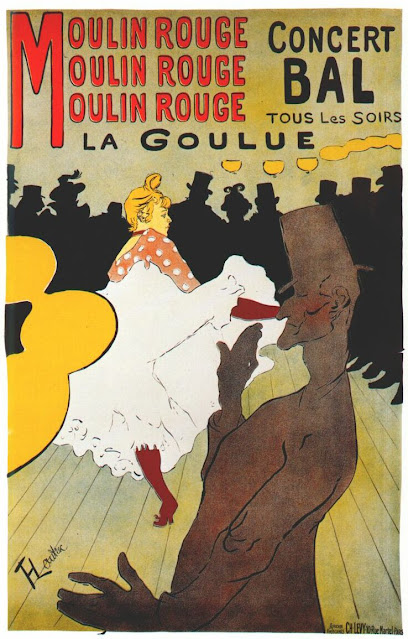

Long before I became so fascinated, when all I really knew about him was watching Jose Ferrer in Moulin Rouge (and by the way, I think he captured Lautrec as well as, or better than, any actor could or should), I had this exact poster on my wall in Alberta. It didn't survive the move, for some reason, though I easily could have rolled it up and stashed it somewhere.

But I was fascinated by the way the background is flipped over into the foreground. The subject of the poster, a garish, rather crude dancer named La Goulou ("the Glutton"), is somewhere in the middle, and in the background we see only black silhouettes of a lot of men and women in hats.

No doubt, these are the delicate classes, slumming, hungry for entertainment that would break every taboo they had ever known.

By placing the weirdly twisted, tree-looking brown man in the very front, it is as if we are in the audience, having to try to look past this ungainly figure to get a good look at La Goulue and the way she kicked so high, you could see that she wasn't wearing any underpants.

This brown man appears in the movie, of course, and everyone complains his prosthetic nose and chin look fake. . . but maybe not.

And ah! In THIS one, not only is the dancer relgated to a smallish figure in the middle, the well-to-do hoity-toities in ther top hats and frilly, furry gowns aren't even looking at her, but justwalking by, promenading, apparently bored. They have come not to see, but to be seen.

Ah, Toulouse, Toulouse. Such a little man. He did cultivate this dapper persona, this half-man who was actually taller sitting down than standing up. I always thought Lautrec was adorable, a sort of doll-man or a puppet, though no doubt he was forced to wear his disability like a badge. Though this seems not to have cramped his style socially or sexually (or, goodness knows, artistically), nevertheless, behind his back, his so-called friends muttered to each other about his shocking appearance.

Not just his body, but his face, which was universally described as coarse and even ugly.

And, of ourse, I am developing a theory about this even as I sit here winging it. Yes, he had a rather large nose and very full lips, which he may have tried to downplay with the shaggy moustache. But the nasty remarks about his huge nose and blubbery lips came directly out of the snobbishness that decreed an "aristocrat" had to look like an aristocrat. What DOES that term mean, facially speaking? A thin, rather aquiline nose, cupid's bow lips, snooty fake-as-fuck eyes that were often half-closed from boredom. Aristocratic, eh what? And Lautrec was none of the above.

I also believe, just as I am sitting here figuring it out, that a large part of it was in fact a kind of racism. His ungainly nose and fat lips, in connection with his black-haired shagginess, made the snooty ones think of Africa, and that was just not the thing, not at all, not at all. In fact, they'd see it as horrifying.

Jose Ferrer compares himself to a monkey in the movie, explaining that beautiful women sometimes kept apes as pets, as they somehow enhanced their own beauty through contrast. No, he didn't look like an ape, an African, or anyone else (well, maybe a bit like King Charles II of Spain! But he couldn't help it if his family rolled around with their cousins.)

His facial features, along with the stunted bandy legs, made him look sort of exotic. And those eyes, which even his detractors had to admit were beautiful, exposed his soul: gentle, compassionate, even tender. It rarely showed in most of his photos, in which his face is oddly unreadable. But he was photographed a lot, and actually liked being photographed, though often in outlandish costumes which meant, in modern parlance, "leaning in" to his strange appearance, making it his "shtick".

He'd make fun of himself, cut ahead of the line, and get the jabs in before anyone else could take a stab.

He could capture the hoity-toitiness of the self-appointed upper crust, but he also exposed the relative emptiness of the well-to-do who flocked to the midnight cabarets for a nice evening of drunken slumming. Their finery did not detract from the hardness of their faces. They could strut around and promenade, and try to outrun being found out - but they could not hide from that little man in the corner, furiously scribbling an image onto a napkin.

And gentlemen, yes, gentlemen, most of them already afflicted with syphilis, looking for a pickup. Why not this one? We can't see her face, but she is pulling back from him noticeably, perhaps appalled by his attentions. And who or what on earth is that apparition between them? A mask, a caricature, or some sort of demon summoned from the depths of the gutter?

This is Jane Avril, played in the movie by Zsa Zsa Gabor, an unlikely choice, though she is the one who sings that divine song. Avril was a real professional and could kick so high her boots touched the ceiling. But she too was all artifice, her own creation, a public persona, and here we see her leaving the threatre, in an unguarded moment looking very alone, and not particularly glamourous.

And yes, Toulouse spent a lot of time in brothels, not just partaking (and one of his nicknames among the girls was Little Coffee Pot), but sketching, and somehow honoring the most stigmatized members of society. Lautrec's working women often looked weary, and he caught them without their come-hither masks on. But he also saw real tenderness between them. The erotic closeness between sex workers gave the women the only real love they would likely ever know.

And this is the real underside, the women lining up for the obligatory medical examination. Not that it did much of anything to halt the spread of venereal disease, but in order to keep their licenses, the madams had to put their staff through this humiliation. And you can see how they feel about it in their faces.

How is it that Lautrec can paint movement like no other painter who ever lived? For you not only hear the swish-swish of the dancer's livid pink petticoats - you feel the breeze, even among the smoke and the fug of the cabaret.

These were the superstars of the fin de siecle - Aristide Bruant with his darkly comic, rather obscene songs written in a kind of crude Parisian patois, Jane Avril getting her kicks (and what could be more phallic than the neck of that huge bull fiddle in the foreground? The musician looks like a maniac or a devil, or perhaps a gargoyle.)

Lautrec liked the crudeness of it, he cultivated it, he sang and praised it, and most of all, he painted it. All of it. His gaze was fierce, and candid, and even compassionate. He saw everything, and got it all down. He sported drag and clown suits and every other disguise that would protect his excruciatingly sensitive interior. It didn't quite work, but disguises never do.

This is the saddest clown I've ever seen. Or is he drunk? For, most of the time, he was, and it killed him, along with the ravages of untreatable syphilis and the raging genetic disaster inflicted by his ancestors, who thought they were such hot shit.

Ah, but here. He's taking in the lavish beauty of this luscious nude model, appreciating it, just thinking about how he is going to capture her body on the canvas, or on one of those great, gaudy, flaming posters that still have the power to jump off the wall and nearly assault you.

Like this one! MOULIN ROUGE! MOULIN ROUGE! MOULIN ROUGE FOREVER!

It is as if Lautrec is the cheering section for a whole era, this so-called Belle Epoque which, as he realized only too well, wasn't too damned belle at all.

There are so many Lautrecs, and that is just the troble. When we think we know what he is trying to do, he pulls this one on us. This woman, heartbreakingly young, her white blouse falling open, having just serviced another customer or contemplating another hard, humiliating day, looks soft and girlish, frighteningly vulnerable. He has, as always caught her in an unguarded moment.

But since life is a cabaret, old chum, the show must go on, and it did, until it didn't. The circus poster featuring the bare horse's ass is somehow, against the odds, beautiful. We sense hoofbeats on sawdust, smell the scatty circus odor of the animals, even get a whiff of the bareback rider's garish perfume. While the man with the whip contemplates, just perhaps, bedding her down at the end of the show.

(Please note. I didn't edit this, and I realize now that some of the paintings and posters appear more than once. It's like that Waldemar guy (who hated the movie, for some reason) asking us to take another look. Or I wasn't in the mood to take the duplicates out, whatever. Toulouse often formally displayed various forms of his masterpieces, even showing preliminary sketches and the same images done in various different mediums. I'm just glad I was able to write this, on a day when I was in more physical pain than I can ever remember. Bonjour, Toulouse, and goodbye.)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments