So my Lautrec Trek continues. Sometimes I think I'm over it (my God, this is like a bad breakup!), and at other times I think it has just begun.

One thing that has kept it going is a novel I'm reading by Pierre LaMure, called, strangely enough, Moulin Rouge. It purports to be the novel on which the 1952 movie is based, but so far it bears little or no relation to that much-loved (by me, not by art critics, who loathe it) film, one of those old-friend movies you like to spend some time with, even if you know how it ends.

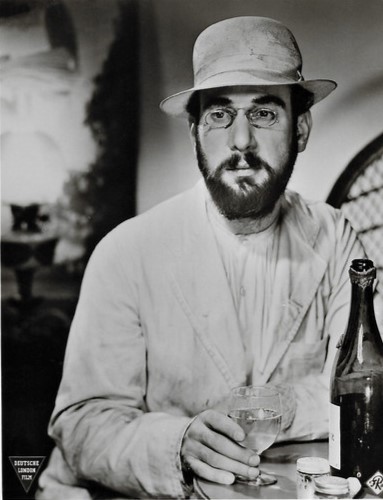

The novel is interesting for the way it DOESN'T truly represent Lautrec, the silly boy behind the gloomy tortured artist, the young wag who dressed up as a clown, an Arab sheik, and a fancy lady in a feather boa, just because he liked having his picture taken. The Julia Frey bio, as bogged down as it is by unnecessary detail, does seem to capture lightning in a bottle, the mercurial, multi-faceted genius who really could go out on the town and have a good time. While at the same time, not whitewashing the fact that he died of a combination of alcoholism and tertiary syphilis.

Though the novel tries to paint him as so chronically lonely as to be almost friendless, the truth is he had a host of loyal and even loving friends, who tried to protect him from the nastiness of social stigma. I think they really did see the value of what they had in Henri, a little man with a huge heart, and an incandescence of vision that would all too quickly flame out.

The Pierre LaMure novel, though I was not able to get much information on it (it seems to be out of print and only available in used copies), is plainly a transation from the French. Though it has touches of brilliance (such as describing a grand piano as "like a coffin for a harp") there's a clunky quality to it, a labored, almost wheezy sense of trudging through detail. French is essentially untranslatable, and the English language, though it 's good for technical things, is lousy for expressing nuance. Only the most brilliant poets can make it jump through hoops of fire and do pyrotechnic tricks. Whoever translated LaMure's novel, and I still can't find out who, lacked that kind of genius and just went word-for-word, making it a bit of a trudge.

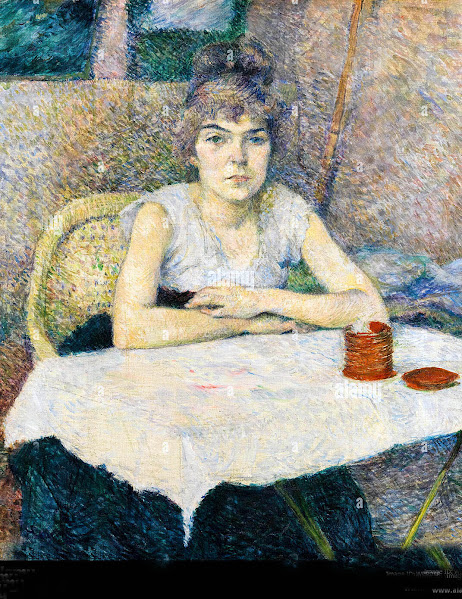

SO: we're left with the paintings, and the drawings, the lithographs, the posters, the immediacy, the startling sense of catching his subjects in mid-breath, as if they are about to turn and speak to you. He not only captured these vulnerable nanoseconds, he captured what they weren't even expressing on their faces or body postures. He got inside them. The little man, no doubt stigmatized for looking so odd, always with thick pince-nez clamped on to his face because he could barely see, saw things in ordinary human beings that no one has ever perceived before or since.

Can I tell you my Lautrec fantasy? Will you be suprised it has nothing at all to do with night life, absinthe, sex in general? I know a little bit of French, what we Canadians call "cereal box French" (meaning, a degree of familiarity due to the bilingual packaging of products), and Lautrec knew a little bit of English and liked to try to speak it. He dressed like a dapper Englishman, albeit one with sawed-off legs, and his mother even called him Henry.

My fantasy is that we're trying to have a conversation, and it's not going well, in spite of the fact that it's totally hilarious and I'm having to sing most of my responses ("Sur le pont, d'Avignon, on y danse, on y danse"). This slightly hysterical exchange is no doubt oiled by Lautrec's famous cocktail, called the Earthquake, consisting of one part absinthe and one part oblivion. As a retired drinker, I don't think I'd really need it to feel the effect.

I want to talk to a man who did the impossible every day of his life. He didn't just paint movement, he painted intent, and even things people had not dared to think in their conscious minds. His paintings are bristling with aggressive and even ugly phallic symbols, demonstrating the fact that men didn't impress him very much, but the women - . His tender studies of courtesans embracing, kssing and cuddling in bed are full of a compassion no one else ever thought of, much less expressed. Compassion, for these harlots? And Lesbians, to boot!

So he knew about contempt, and how easily and casually you could become the target of it if you did not quite fit the social prisons of the day. He saw and saw and saw, mainly how people somehow found love and expressed love in the midst of an ugly, harsh, unyielding environment where everything was for sale. Much as he was famous in his lifetime, he may even have craved anonymity, turning back the clock to simpler times when not so much was expected of him.

This is his most famous poster, the one that started it all, and as usual it's topsy-turvy, forcing us to look over the shoulder of this great hulking monster in the foreground to get a glimpse of the wild cancan dancer La Goulue, the real subject of the work. As a backdrop we see black silhouettes of high hats both male and female, and on the left is a wildly distorted electric light.

And that's another thing. Lautrec was the first artist to paint electricity - that garish new phenomenon that revealed things we never expected to see. Suddenly the soft gaslight was wiped out, the newfangled illumination exploding like lightning in a way that must have seemed like a violation. It's why the grotesque carved-from-chocolate man in the foreground is in shadow, and only the dancer in the middle is lit up, scandalously displaying her crotch to all and sundry. Her lower half lights up the room, electric lamps making her lacy plus-fours flare and glare. Did any artist of his day dare to display a massive phallic hand just inches away from a nearly-bared female crotch?

The fact that it's beautiful is another mystery, another impossibility, like that wacky Franglish conversation I want to have with Henri. He was gone too soon, but while he was here - while he was here -

.jpg)