This is a literal translation from a lovely site called Russian Culture. It's one of the best "Life of Gershwin" pieces I've seen because the prose is so delightfully wonky. It's as if you can hear someone with a heavy Russian accent telling the story with great enthusiasm. I omitted the original photos because we've seen them all before, and tried to substitute something slightly more imaginitive.

http://allrus.me/russian-jewish-heritage-george-gershwin/

Russian Jewish heritage George Gershwin. September 26, 1898 in New York City in a family of immigrants from Russia, was born a boy Yasha. The whole world knows him as George Gershwin – self-taught musician of the 20th century and the King of Broadway and Hollywood musicals.

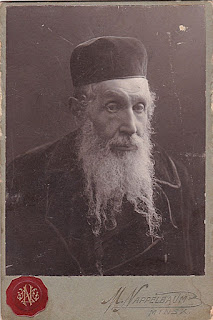

Gershwin came from Russian Jewish heritage. His grandfather, Jakov Gershowitz, had served for 25 years as a mechanic for the Imperial Russian Army. He retired near Saint Petersburg. His teenage son, Moishe Gershowitz, worked as a leather cutter for women’s shoes; Moishe fell in love with Rosa Bruskin, the teenage daughter of a Saint Petersburg furrier. Bruskin moved with her family to New York, she Americanized her first name to Rose. Moishe, faced with compulsory military service in Russia, followed Rose as soon as he was able.

George Gershwin grew up a tomboy street, to say, a bully, and also studied badly! “Lord, what comes out of this boy!” – pathetically exclaimed dad Gershovich. Everything suddenly changed when at a concert in the school Yasha first heard the famous violinist Max Rosenzweig. One and a half hour after a concert George was waiting for the soloist, ignoring the pouring rain, having found that he had gone the other way, rushed to his home.

They became friends. “Max introduced me to the world of music” – recalled the composer. At the home of Rosenzweig George taught himself to play the piano by ear picking popular tunes. The parents repeatedly tried to hire teachers to him, but George couldn’t get along with them. He remained self-taught.

At 15, George Gershwin found work as a pianist-accompanist at the publishing house “Remick & Co”. Soon he entered theatrical circles, and in 1918 presented his first musical on Broadway. It all ended in failure, however, the young man was not discouraged. He literally filled up Broadway producers with his works.

Finally, in 1924, George Gershwin was lucky. Musical on his music, «Lady, Be Good» has become a real Broadway hit. For this show Gershwin wrote the song, which many consider to be one of the best love ballads of the 20th century – «The Man I love».

By the way, this song, like almost all the songs and musicals of George Gershwin, were written on verses of his older brother Ira – a professional poet and writer. “Rhapsody in Blue” and the musical «Lady, Be Good» brought good money. This allowed the family to move out of the provincial district to their own five-story building at 103 Street and George – a journey through Europe.

In Paris, he met the famous French composer Maurice Ravel, and even tried to persuade the master to give him a few lessons in composition:

– But why study? – Asked Ravel. – You’re already famous. How much do you earn?

– One hundred thousand dollars a year – sheepishly replied Gershwin.

– Awesome! – Exclaimed Ravel – then I’d have to take lessons from you!

From a trip to Europe Gershwin returned with a sketch of the symphonic poem “An American in Paris.” It was sung in the Philharmonic Society of New York and happily forgotten. Many of the brothers Gershwin tunes were later used for writing songs. Well, in 1951, when George was no longer in the world, director Vincente Minnelli made a wonderful musical “An American in Paris” by Gershwin brothers songs. “An American in Paris” is still consistently ranks in the top five films of musicals of all time. By the way, the musical features one more hit of Gershwin «The Foggy Day»

They say that time puts everything in its place! Today George Gershwin is recognized genius of the 20th century. However, praise and serious musicological articles and books obscure the image of Gershwin – cheerful, amorous, thoughtless man, besides a brilliant storyteller and inveterate wit. And, of course, Gershwin never married, he was Don Juan. His affair with actress Paulette Goddard (whom he begged to leave her husband Charlie Chaplin), a French film star Simone, beautiful dancer Margaret Manners, Marguerite Eriksen, Kay Swift, Mollie Charleston – were the main topics of gossip at the time. However, numerous romances, according to Gershwin, were the main source of his inspiration. Generally, in the twenties and thirties Gershwin created musicals one after the other.

Many people are still arguing about the genre of the work. What is this, an opera or a musical? Or maybe something else? It is, of course, the “Porgy and Bess” – A masterpiece by George Gershwin. However, the composer said: “The main thing that the public liked, and genre … the genre is not important.”

Gershwin’s life ended abruptly and tragically. What began with a simple headache, suddenly turned into a chronic and serious disease. When Gershwin began to forget the whole parts of his works, his friends and relatives advised to go to the doctor, who diagnosed a “brain tumor” and advised surgery. The surgeon, specializing in transactions of this kind, was on his way to California to save the life of his illustrious patient, but he was too late -11 July 1937, George Gershwin died

His music still sounds in Broadway shows, Hollywood George Gershwin. His songs are still big hits. Additional facts from Russian Wikipedia: One of the hobbies of Gershwin was drawing. Gershwin was in love with Alexandra Blednykh – she was his best pupil.

Gershwin never married, but he had an only son. Alan Gershwin (b. 1926) was the son of George Gershwin and showgirl Margaret (“Mollie”) Manners. Paul Mueller, Gershwin’s valet, recounts trips made by Gershwin to visit Margaret and the boy, and says that he had no doubt the boy was his son. He also recalls trips made late at night, “undercover,” to the boys home in California. Alan Gershwin recalls receiving regular visits from his famous father growing up, and he received envelopes of cash with each visit to help support him. Peyser provides convincing evidence and reports that Alan Gershwin was actually Gershwin’s son – although the Gershwin family still denies it. Peyser suggests that Ira and Leonore denied Alan’s claims in order to keep him out of George’s inheritance, but once paid him $300 K to keep quiet and leave them alone. (from Joan Peyser’s account of George Gershwin in “The Memory of All That”)

Visit Margaret's Amazon Author Page!