Artists struggle to survive in age of the blockbuster

RUSSELL SMITH

Special to The Globe and Mail

In the artistic economy, the Internet has not lived up to its hype. For years, the cybergurus liked to tell us about the “long tail” – the rise of niches, “unlimited variety for unique tastes” – that would give equal opportunities to tiny indie bands and Hollywood movies. People selling products of any kind would, in the new connected world, be able to sell small amounts to lots of small groups. Implicit in the idea was the promise that since niche tastes would form online communities not limited by national boundaries, a niche product might find a large international audience without traditional kinds of promotion in its home country. People in publishing bought this, too. The end result, we were told, would be an extremely diverse cultural world in which the lesbian vampire novel would be just as widely discussed as the Prairie short story and the memoir in tweets.

A couple of prominent commentators have made this argument recently about American culture at large. The musician David Byrne lamented, in a book of essays, that his recent albums would once have been considered modest successes but now no longer earn him enough to sustain his musical project. That’s David Byrne – he’s a great and famous artist. Just no Lady Gaga. The book Blockbusters: Hit-making, Risk-taking, and the Big Business of Entertainment, by business writer Anita Elberse, argues that the days of the long tail are over in the United States. It makes more sense, she claims, for entertainment giants to plow as much money as they can into guaranteed hits than to cultivate new talent. “Because people are inherently social,” she writes cheerily, “they generally find value in reading the same books and watching the same television shows and movies that others do.”

Well, the same appears to be true of publishing, even in this country. There are big winners and there are losers – the middle ground is eroding. Publishers are publishing less, not more. Everybody awaits the fall’s big literary-prize nominations with a make-us-or-break-us terror. Every second-tier author spends an hour every day in the dismal abjection of self-promotion – on Facebook, to an audience of 50 fellow authors who couldn’t care less who just got a nice review in the Raccoonville Sentinel. This practice sells absolutely no books; increases one’s “profile” by not one centimetre; and serves only to increase one’s humiliation at not being in the first tier, where one doesn’t have to do that.

Novelists have been complaining, privately at least, about the new castes in the literary hierarchy. This happens every year now, in the fall, the uneasiness – after the brief spurt of media attention that goes to the nominees and winners of the three major Canadian literary prizes, the Scotiabank Giller, the Governor-General’s, and the Rogers Writers’ Trust. The argument is that the prizes enable the media to single out a few books for promotion, and no other books get to cross the divide into public consciousness. And, say the spurned writers, this fact guides the publishers in their acquisitions. Editors stand accused of seeking out possible prize-winners (i.e. “big books”) rather than indulging their own tastes. This leads, it is said, to a homogenized literary landscape and no place at all for the weird and uncategorizable.

But even if this is true, what can one possibly do about it? Abolish the prizes? No one would suggest this – and even the critics of prize culture understand that the prizes were created by genuine lovers of literature with nothing but the best intentions, and that rewarding good writers financially is good, even necessary, in a small country without a huge market.

It’s not, I think, the fault of the literary prizes that the caste system exists. Nor of the vilified “media” who must cover these major events. It’s the lack of other venues for the discussion and promotion of books that closes down the options. There were, in the nineties, several Canadian television programs on the arts. There were even whole TV shows about books alone. Not one of these remains. There were radio shows that novel-readers listened to. There were budgets for book tours; there were hotel rooms in Waterloo and Moncton. In every year that I myself have published a book there have been fewer invitations and less travel. Now, winning a prize is really one’s only shot at reaching a national level of awareness.

So again, what is to be done? What does any artist do in the age of the blockbuster? Nothing, absolutely nothing, except keep on doing what you like to do. Global economic changes are not your problem (and are nothing you can change with a despairing tweet). Think instead, as you always have, about whether or not you like semicolons and how to describe the black winter sky. There is something romantic about being underground, no?

Look on the bright side: Poverty can be good for art. At least it won’t inspire you to write Fifty Shades of Grey.

A couple of prominent commentators have made this argument recently about American culture at large. The musician David Byrne lamented, in a book of essays, that his recent albums would once have been considered modest successes but now no longer earn him enough to sustain his musical project. That’s David Byrne – he’s a great and famous artist. Just no Lady Gaga. The book Blockbusters: Hit-making, Risk-taking, and the Big Business of Entertainment, by business writer Anita Elberse, argues that the days of the long tail are over in the United States. It makes more sense, she claims, for entertainment giants to plow as much money as they can into guaranteed hits than to cultivate new talent. “Because people are inherently social,” she writes cheerily, “they generally find value in reading the same books and watching the same television shows and movies that others do.”

Well, the same appears to be true of publishing, even in this country. There are big winners and there are losers – the middle ground is eroding. Publishers are publishing less, not more. Everybody awaits the fall’s big literary-prize nominations with a make-us-or-break-us terror. Every second-tier author spends an hour every day in the dismal abjection of self-promotion – on Facebook, to an audience of 50 fellow authors who couldn’t care less who just got a nice review in the Raccoonville Sentinel. This practice sells absolutely no books; increases one’s “profile” by not one centimetre; and serves only to increase one’s humiliation at not being in the first tier, where one doesn’t have to do that.

Novelists have been complaining, privately at least, about the new castes in the literary hierarchy. This happens every year now, in the fall, the uneasiness – after the brief spurt of media attention that goes to the nominees and winners of the three major Canadian literary prizes, the Scotiabank Giller, the Governor-General’s, and the Rogers Writers’ Trust. The argument is that the prizes enable the media to single out a few books for promotion, and no other books get to cross the divide into public consciousness. And, say the spurned writers, this fact guides the publishers in their acquisitions. Editors stand accused of seeking out possible prize-winners (i.e. “big books”) rather than indulging their own tastes. This leads, it is said, to a homogenized literary landscape and no place at all for the weird and uncategorizable.

But even if this is true, what can one possibly do about it? Abolish the prizes? No one would suggest this – and even the critics of prize culture understand that the prizes were created by genuine lovers of literature with nothing but the best intentions, and that rewarding good writers financially is good, even necessary, in a small country without a huge market.

It’s not, I think, the fault of the literary prizes that the caste system exists. Nor of the vilified “media” who must cover these major events. It’s the lack of other venues for the discussion and promotion of books that closes down the options. There were, in the nineties, several Canadian television programs on the arts. There were even whole TV shows about books alone. Not one of these remains. There were radio shows that novel-readers listened to. There were budgets for book tours; there were hotel rooms in Waterloo and Moncton. In every year that I myself have published a book there have been fewer invitations and less travel. Now, winning a prize is really one’s only shot at reaching a national level of awareness.

Look on the bright side: Poverty can be good for art. At least it won’t inspire you to write Fifty Shades of Grey.

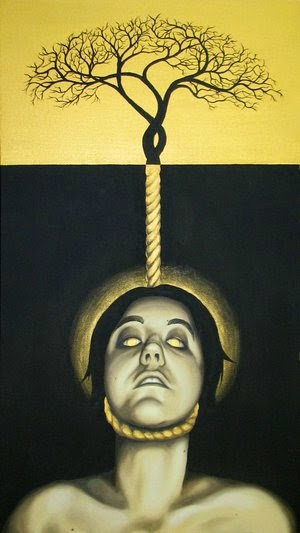

BLOGGER'S NOTE. I re-ran this article strictly to make myself feel better. I was surprised to see how old it is, but in three years, things have only gotten worse. Strangely enough, it helps. It helps me feel that maybe-just-maybe I'm not the only one, though talking about failure is the greatest taboo and career-sinker there is. I don't remember seeing a single article about it on the internet, except for "oh, I was such a failure" followed by "but here is what I did to overcome this failure and find soaring success." Failure is something that really doesn't happen unless you go on to succeed, right? This is reflected by all those chirpy little Facebook memes about failure being a wonderful thing that you should "embrace", not be afraid of, and see as a stepping-stone to greater and greater victories. But what if it doesn't happen that way?

When this article first came out, I felt a tremendous amount of comfort in these words, but it's the only piece I've ever found that dares to criticize the industry. Or something. The whole system? In no way, shape or form do I blame individual publishers for this state of affairs, because they're just trying to survive. It's a juggernaut, and if "numbers" are any indication (and sheer numbers of "likes" and "stars" are now the ONLY measure of a writer's worth), I've failed.

I've seen fellow writers strive and strive and hurl their work at the wall, and once in a while it cracks. I'm not so sure I am willing to do that. The system was always hard, but it wasn't impossible. I didn't sell a huge number of copies of my first two novels, but I guess you could say they were critically well-received. "Fiction at its finest" from the Edmonton Journal now seems particularly heartbreaking. The Montreal Gazette books section gave me an entire page, with (mysteriously) a huge picture of me in colour, and said this book deserved to be on the bestseller list but never would be, because it was published and publicized on such a small scale. So the praise was sort of backhanded, after all, and only set up false hopes.

I thought I had a shot.

I didn't, and I know now that it would've been better, if I wanted TGC to see the light of day, to just set up a blog for it and hope for the 10 - 25 views I usually get. But it's 10 - 25 more views than I'd get if I did nothing.

I can't lie in wait any more. I have to "move on", wherever "on" is. "Let go", and not "let God" because there isn't one, though I was a lay minister and taught Bible classes for fifteen years. Now THERE is a story of heartbreak, but I didn't just make it up out of my own head.

I know I don't make myself popular by getting into this stuff, as it's seen as "being negative", which is a big no-no no matter how dire things are. Just paste a smile on and keep turning that facet of yourself towards the world/social media (though turning and turning and turning it like that can be completely exhausting). People who are seriously interested in writing (or becoming writers, which is another thing entirely) want to believe that I am an anomaly. I suspect I'm not. The difference is, I talk about it, openly admit I have failed, and no one else does. If somebody tells me not to do something, I will immediately want to do it. And usually I do, fuck the consequences, because as a writer, it is all I have. Shouldn't I be able to write about anything I want or need to? I will continue to, whether it is popular or not. It does not matter, in the long run. In the world's terms, success will never come to me, even though I have been told over and over again that I have the "right stuff".

So I will write whatever comes into my head. No law against it. And I can guarantee it will always be honest and tell my truth, whether it would fit on a Facebook meme or not.