This is a serialized version of my novel Bus People, a story of the people who live on Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. The main character, Dr. Zoltan Levy, is loosely based on author and lecturer Dr. Gabor Mate. It's a fantasy and not a sociological treatise: meaning, I don’t try to deal with “issues” so much as people who feel like they’ve been swept to the edge of the sidewalk and are socially invisible/terminally powerless. I’m running it in parts, in chronological order so it’s all there, breaking it up with a few pictures because personally, I hate big blocks of text.

Bus People: a novel of the Downtown Eastside

Part Two

"No one is as capable of gratitude as one who has emerged from the kingdom of night." Elie Wiesel

Portman Hotel, Vancouver, B. C.

September 7,

2003

Cylinders. The backpack was full of

cylinders. It was not full of

junk. Not not not. And they’re not just any old cylinders,

they’re Edison Blue Amberols, the best kind you can get.

I

have to find more Blue Amberols. It’s

just a habit, I can quit any time I want to, just a little quirk of mine,

collecting. I collect all sorts of

stuff, birdcages made out of bamboo, salt-and-pepper shakers shaped like

people, macramé handbags made back in 1973.

My room here is full of stuff,

the social worker doesn’t like it, she complains about it all the time

and keeps telling me to clean it up, get rid of it all. But it’s cool, there’s no rats or anything,

it isn’t dirty, I keep order in the place.

Sometimes stuff falls down, there are loud crashes at night that disturb

the neighbours, particularly Porgy who lives just under me and is a light

sleeper. But at least I know where

everything is.

I didn’t even know what a Blue Amberol was

until I started going to flea markets about a year and a half ago. I saw these ornate-looking canisters with

flowery writing and ornamentation all over them – they were beautiful, and I

just had to buy one of them, not even knowing what was inside. It was only a buck and a half, what the hell,

I’ll go without lunch tomorrow. Maybe

it’s snuff or something, I thought, something Victorian, or at least Edwardian,

really old and maybe even valuable.

But it wasn’t snuff at all. It was a dusty old cylinder full of

grooves. Took me a minute to figure it

out, that this was something like a record, or what came before records, the

first medium for recorded sound. I felt

like I had seen one before, that I remembered it from somewhere. I had Porgy go on the internet and do a

search. I don’t have a computer, I don’t

know how Porgy can afford one, but he does and is obsessed with it.

Anyway, he tells me that this isn’t just

any sort of flea market hunk of junk but

a Blue Amberol, a particularly deluxe (back then) kind of cylinder recording

popular in the early 20th century.

They weren’t the earliest recordings – those were made out of brown wax,

with a few really early, rare ones made out of yellow paraffin, but even before

that, they used tin foil. No kidding – tin

foil on a rotating cylinder, scratched with a needle that picked up

vibrations. The basic principles of

sound recording. Think of Thomas Edison

at Menlo Park, bellowing into his new contraption: “MA-RY HAD A LIT-TLE LAMB. ITS FLEECE WAS WHITE AS SNOW. AND

EV-ERY-WHERE THAT MA-RY WENT, THE LAMB WAS SURE TO GO. HA, HA, HA.”

Cranking away at a variable speed, so the voice sounds freaky, all

distorted like a giant’s voice, as well as tinny and really far away.

When I was little, old records used to

scare me. I used to think. . . never

mind what I used to think. I had a hell

of an imagination. It got me in trouble all the time, at school, but even worse

at home. My mother used to say that I

made up stories, but to me, it was all completely real. I thought the voices on those old 78 r. p. m.

records had some sort of spooky power.

Like it was a kind of time capsule or something. The singing ones were weird enough, they all

had that muffled quality like the sound was coming out of a tiny little

closet, but the spoken word ones, they

really freaked me out. Used to make me

run out of the room, but my Dad, he’d make me listen to them, listen to Caruso

sounding like he was singing inside a cardboard box, or Dame Nellie Melba

warbling away, or something called the Wibbly-Wobbly Walk – God, the Wibbly-Wobbly

Walk scared the living shit out of me.

Couldn’t stand it, but my Dad made me stay and listen.

It was his collection and he was convinced

it was worth thousands, but now that I know something about early recordings, I

can see that what he had was virtually worthless. Too many scratches, ticks and

pops.

Dr. Levy, the one they call “Zee”? He’s

helping me deal with memories. He’s

good. I mean, he’s good if you’re in

pain or trouble, if you’re not, then forget about it, he can be a real hardass,

it’s surprising how cold he can be. But

I’ve seen him deal with guys so far gone from AIDS, the shit was pouring out of

them like lava, and he never bats an eyelash, just rolls up his sleeves and

cleans up the crap like it was nothing.

I like Dr. Levy.

But this guy on the bus today, this

Szabó. I know that’s his name, because

people talk about him. He has regular

habits, I’ll say that about him. I don’t

know where he goes exactly, somewhere around the Sunshine Hotel area, the real

asshole of Vancouver, Zeddyville they call it, ‘cause Dr. Zee cruises the place all the

time, looking for broken people to mend.

It’s his habit.

Mine’s Blue Amberols. I’m glad this Szabó can’t look at me, because I just hate it when people stare at

my backpack, poke at it or ask what’s inside it. I had fourteen Blue Amberols crammed in there

today, and never mind that I haven’t

been able to afford a player yet, it’s only a matter of time.

I

guess listening to these things is going to scare the living shit out of

me. I take five hundred milligrams of

Seroquel every day, Dr. Zee is trying to wean me off it, he says I might have

been misdiagnosed, but I’m not so sure about that, I guess you could say I

scare easily, I was born minus a few

layers of skin. But this Szabó, he has

no face, or that’s what they say about him anyway, even though he sings. I’ve heard it, we all have. He sings without words, of course: “nggg, nggg, nggg” – it’s creepy, but

you know something, he has a good voice, and a Hungarian accent, even with no

words. I wish he’d go see Dr. Zee, he’d

be able to help him. That guy could’ve

helped Hitler get over his anger problem.

Maybe he could write things down on a piece of paper or a chalkboard, I

don’t know. Better than begging, which

is what Szabó does for a living now that he can’t see to paint. It’s sad.

I draw a disability cheque, it’s not much but it keeps me going, along

with whatever stuff I can make or sell or trade, even though I’m not allowed to

see my kids which sometimes makes me want to slit my fucking throat, just end

this, end it now. But Dr. Levy

says don’t, Dr. Levy says don’t think that way, he says I’m valuable, he says

there’s only one of me in all the world, that human beings are irreplaceable,

so I guess I better trust his judgement which might be just a little bit

clearer than mine.

Anyway, Szabó gets on the bus this

morning, it’s one of those stinky wet mornings when everything’s dripping, and

he sits right down beside me like he’s done so many times before. Like I say, regular habits. And Szabó is clean, not like a lot of the

people who take the bus every day; he doesn’t ever smell, he looks after

himself. I don’t know how he does it, but he does. Pride. He must have hair still, I mean, the back of

his head must still be OK, just his face is missing, no big deal, nothing serious, eh? But then a guy across from us on the sideways

seats says, “Hey, fucking freak, you on a pass from the sideshow? Gettin’ it on

with the Schizo Lady?” Street people

have got radar, that’s how they can tell.

“I beg your pardon, buddy, if you wanna

see a freak, I think you should maybe try looking in the mirror.” I’m usually not this bold, but poor Szabó

can’t speak up. Can’t defend himself,

but he can hear everything. It’s

cruel. This guy across from us, he looks

like a bad bowel movement after too many blueberries, long and snaky and

tattooed dark indigo all over every square inch of his skin. He’s a living shit. And he’s calling us freaks. Jesus.

I keep trying to tell Dr. Levy what it’s like, but he just shakes

his head. Says people call him a Kike or

a Yid or a Heeb sometimes, but it’s not the same, it’s not. “Hey! Auschwitz!” one of them said to him once – and, yeah, he is pretty

thin, looks kind of undernourished. How does that go? “He hath a lean and hungry look.”

So the driver, his name’s Bert Moffatt, I

know him ‘cause I’ve seen him lots of times before on the Number 42, he says to

me, “Lady, would you kindly can the comments, you’re being abusive here.” I’m being abusive. If a schizo lady raises her voice even a

little bit, she’s being abusive, she’s out of control, while this big

blue-tattoo shithead over here, he can hurl insults at anybody he likes. Why? I don’t know, I guess he’s supposed to

be sane. Probably a pimp, probably a

heroin addict or a child molester or sells his grandmother for a hit of crack,

but he’s allowed to say whatever he likes.

Fuck it, I’m going back to the flea market

tomorrow and buy that cylinder player I saw, it was priced at $75.00 which for

me is a bloody fortune, and it looked busted, the ones that work cost way more

than that and are out of my price range, but you can usually bargain with these

guys, and I have $50.00 scraped together already, it took me months and months

of going without smokes, and then I found a ring in the washroom at the

Tinseltown Theatre, pawned it and got nearly 30 bucks for it which goes to

prove that there is such a thing as Providence. Porgy keeps me going on smokes, enough to

stave off the worst of my nicotene fits, he’s cool about things like that, even

though he never goes out, he’s glued to the internet all the time, reading up

on mucoid plaque and colonic irrigation.

What a nut. But he’s still kind

of sweet.

Zeddyville

They call it Needle Park, they

call it Pigeon Park, they call it Zeddyville because that’s where Dr. Zee hangs

out: and it’s not a park at all, but a

vaguely triangular slab of cement crusted in pigeon shit, draped and clustered

with people nobody seems to want around.

It’s a loitering sort of place, an unplace. A dislocation. Calling it a park is an

impossible stretch, for no green thing could grow here. Dr. Zoltán Levy barely notices it any more.

He has a very fast walk, but it’s not so he can get away from the horrors of

the neighborhood. It’s so he can zip

from the Portman to the Sunshine to the Waverley Hotel to get to his patients,

the people who are usually on their last gasp.

Dr. Zee doesn’t step on the bus very

often, but it disgorges passengers right outside his home base, the Portman, an

armoured truck of a place, fortified, barred, battened down like the good

doctor’s own bleak, unsmiling face. He

makes himself available to people, people like Aggie Westerman the chronic

schizophrenic, and Porgy Graham who has a strange obsession with his bowels, and Dave the

mutilator who has his lips multiply pierced and chained together, so he can’t

even eat without pulling all the studs out.

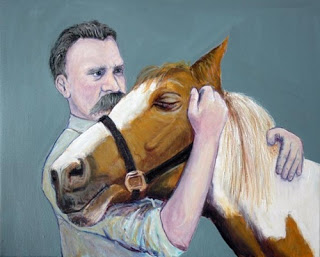

Things happened to Dr. Zee a long time

ago, everybody knows that, or at least they suspect it, though no one has any

specifics, and he isn’t talking. He

“doesn’t have time for a relationship”.

That’s what he says when he is interviewed, which happens quite a lot

now, because slowly but surely, Dr. Zee is

starting to become famous. At

least, Vancouver famous, and maybe soon, Canadian famous, then the world. He is working on a book that is taking him

forever to write because he really doesn’t want to finish it, it’s got too many

secrets in it, and he hates to make himself so vulnerable. Yet he loves the vulnerable, holds his hands

out to them, thick-fingered veterinarian’s hands that look as if they could

pull out calves and shoe horses. He gets

what it is to be this hurt, this lost, and to keep on going.

People ask him, often, if the work is

depressing. What depresses him is the

question: the implication that he is

dealing with the dregs of humanity, and not a whole lot of bruised little kids

in adult bodies, people who were fucked by their fathers or whipped senseless

by their mothers or told they were useless piles of shit so often they began to

believe it, or told that they never should have been born at all. It does a bit of damage when you hear it

often enough; it can warp a life into a howling parody, heroin squirting up

through the veins to blot out the self-loathing for just a little while, a

protected, peaceful while, until it’s time to start hustling again. The abyss

of the heroin state is welcome, oblivion being far more bearable than whatever

is in second place.

Tourists come to Zeddyville because the

area is a little bit famous, too, kind of like Dr. Zee himself, and even the

Governor-General came once, on a walkabout like the Queen Mother, her face in a

carefully-composed mask of what she hoped was concern. It doesn’t smell too good down here, it

smells like rancid piss at the best of times, human vomit, pot fumes and other

things you can’t identify. It’s a raw wound, the walls of the buildings

splattered in gory-colored murals and gang graffiti impossible to decipher, the

strange hieroglyphics of the street. You

have to keep your cool in Zeddyville, not show any fear. It helps not to make eye contact, as you’ll

stare into an abyss, a vacuum, an absence in the eyes of every stranger that

passes by.

“Spare change? Spare change?

Have a nice day. Spare

change? Spare change? Have a nice day.” It’s a sort of mantra for a lot of people, a

way to make it through to the next day of spare change, spare change, have a

nice day. Of course some of the

people here are crazy. There used to be

a place called Valleyview, but they closed it down except for the really

hard-core cases, and shouldn’t these people be integrated into the community

anyway and not just institutionalized and kept out of the mainstream, hidden

away like they’re frightening or shameful?

Now the dirty little secret of mental illness is an open secret, like

Szabó’s face when it was shot off and blown to bits all over the blackened

walls of his torched studio. The walking

wounded don’t have their intestines hanging out all over the outside of their abdomen, like in a war, but

they do have spilled psyches, their pain hanging out, their loneliness hanging

out, and it bothers people, the normies, the civilians. Their faces broadcast

what they feel: for God’s sake get

away from me buddy before I see myself again, before I see what’s really wrong

with me and why I cannot find a place in this world, before I see that this is

where I really belong.

For no matter how good I look on the

outside, I am part of this whole deal that creates a Zeddyville in the middle

of a glittering, prosperous, showcase city on the coast of the best country in

the world, then forces people to live in it when living is just a simple, bare

act of endurance.

We shove them here, we forklift,

steamroll, corral, push, shove, cram, then clang the gate shut behind them and

then say, what’s wrong with these people, why can’t they get it together,

why can’t they make something of themselves?

Get a job!

Leave me alone!

NO, I don’t have any spare change, and put

that squeegee away because I am not interested in the fact that you haven’t had

anything to eat for four days! Jesus,

these people.

Dr. Zee sees, hears, senses it all the

time, a palpable sense of dismissal and fear echoes all around him, the long

antennae sticking out of his head pick it all up, whether he wants to hear it or not, but he

keeps on walking fast with his stethoscope going bounce, bounce, bounce on his

chest. He doesn’t really have one around

his neck, it just appears that way, it’s his sense of purpose, so intense and

focused, it’s almost a buzz. He doesn’t

carry a black bag either, but he will go where the trouble is, he will go where

the pain is, and down here, there is more than enough to go around.

Bus People Part One

Bus People Part Two

Bus People Part Three

Bus People Part Four

Bus People Part Five

Bus People Part Six

Bus People Part Seven

Bus People Part Eight

Bus People Part Nine

Bus People Part Ten

Bus People Part Eleven

Bus People Part Twelve