This is one of those experiences that is impossible to describe. Just a manifestation of my desire to connect with a meaningful God? You decide.

After much anticipation, I finally went and saw Nowhere Boy, the movie (drama, not documentary) about John Lennon's youth and his troubled relationship with his Aunt Mimi (who raised him) and his mother Julia, an unstable but charming woman who gave him up due to complicated circumstances. At the same time, the musical ferment that gave rise to the Beatles begins to bubble and seethe. John starts a crude, amateurish "skiffle" group (Liverpudlian folk/rock), of which he is definitely the leader, though his guitar skills are poor, and his classmates from art school are worse.

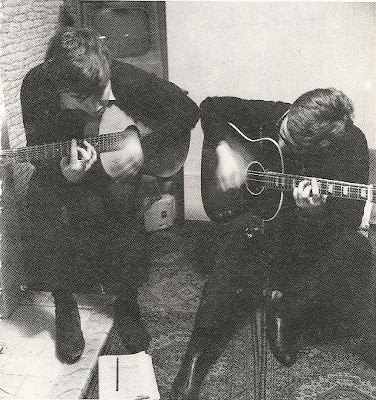

Then he meets a baby-faced 15-year-old named - well, do I need to tell you? Paul holds the guitar left-handed, and plays rings around everyone else. Jealous, John at first turns him away, but soon starts to work on his skills with him.

The movie was slow to start, and the actor who played John (not a name I'd heard of) was not very convincing at first, as he seemed sort of passive. But as the story unfolded, you bought him more and more. When he picked up a guitar, a fierceness came over him, and by the end I was thinking, that's John Lennon.

Of course we know what will happen. John's wayward Mum Julia dies at the end, hit by a car, just as she is making peace with the family. Paul has just lost his mother to cancer, so now they are brothers in nearly every sense.

The movie was powerful, and I was quite moved to see Yoko Ono listed as a consultant in the credits, which kept it honest. It was reviewed as a "kitchen-sink drama a la Coronation Street", and it did have elements of that. But Kristin Scott Thomas as Aunt Mimi was spot-on perfect in establishing sympathy for an unsympathetic character. She deserves an Oscar for her courage and skill.

But the weird thing happened at the end. During the credits I started to cry unexpectedly, then I was really sobbing. Fortunately, nearly everyone had left. Then I felt this - I will try to describe it. A "presence" behind a sort of screen or very thin veil. It was slightly to the left, about halfway between me and the front of the theatre, and angled a little bit, slightly diagonal. Something like very thin gauze, or a translucent veil. I heard a voice without words that conveyed something very powerful. In essence it said, how can you not believe in me when I am right in front of you? You have stopped believing in a God, and yes, that God may not be in a church, but he's right here, Margaret, right here (indicating my chest) in your heart.

I was stunned and doubtful and electrified and wondered what it really meant, but I was not going to turn it away. It wasn't the first time I've had experiences that I can only describe as psychic, but I wondered what in the world this "voice" (undoubtedly his) would ever want with a nothing like me. The presence was so large it filled the whole theatre and extended past the walls. I can't really describe what it was like. Any words seem wrong or inadequate. I finally left and went to the ladies' room (fortunately empty) and just sobbed and sobbed, wondering if this was somehow connected to my brother Arthur's death in 1980, only two months before John Lennon was shot and killed.

I never expected this, didn't want or need or call for a lesson in theology or the true nature of God or whether or not we survive our bodies. In fact, I'd just about given it up. I was beginning to think we just die, get put under the ground, and that's it, it's all over. I was starting to really believe there's nothing there, nothing that loves or cares about us as individuals. For a former practicing Christian, this sort of spiritual abyss was agony, but I could not fix or change it. This presence, familiar yet strange, didn't really explain all that, but just manifested and asked me: I am right here, so how can you not believe?

I can try to worry this down to nothing, or intellectualize, or throw it out. I've had a bit of time to process it. I will accept it as valid, whatever it means. I have been told, apparently, that we DO survive our bodies and that that individual energy still exists very powerfully. As with all these things, I was afraid that If I told anyone they'd just scoff and say, why was it someone so famous? What makes you think - ? But why not? I'm receptive, and after that heartbreaking movie I was wide open, all defenses down.

Anyway, so many people want or desire or ask for psychic experiences and think they'd be really wonderful, when in fact they can be a bit of an ordeal, in that you question your sanity or at least ask yourself if it was merely a projection of your own desires or your imagination. So I share it with you, just as it was.

.jpg)

.jpg)