Ah, those days: the days of Johnny Larue and William B. and Dr. Tongue and all the other surreal characters taken over by John Candy. For the characters didn't take him over - it was the other way around. He invaded them and became.

Johnny LaRue, the chimney-smoking, booze-swilling, dame-exploiting would-be politician of Melonville was one of my favorites. In this clip he pitches himself as a candidate for City Council, and even that untidy flop of hair is reminiscent of Donald Trump, along with all the ranting bullshit.

But LaRue had a signature phrase he used in every sketch: "And I'm not gay!" I was reminded of this when I opened my email this morning and found a comment from someone about my Alan Gershwin post (which got a good response, believe me, in light of the 13 views I get for some of them). The reader vehemently denied any suggestion that either George or Alan Gershwin was gay. This is typical of the indignant, deeply insulted, even infuriated tone of people who perceive any such suggestion in biographies of famous (and usually it's) men.

Lost and Found: the mystery of Alan Gershwin

No one ever thinks - it doesn't occur to them even for a moment - that their fury reveals the slightest degree of homophobia. But even a suggestion the person in question MIGHT have been gay is automatically seen as vicious slander which has to be vigorously denied and argued into the ground. No, he was NOT "one of those". There is no EVIDENCE he was "one of those". He had hair on his chest, for God's sake! Don't defile his good name like that!

What???

I'm not defiling anything or anyone when I say there were suggestions that Gershwin might have been gay. Most of his biographers (including Howard Pollack, who wrote a definitive 885-page doorstop) have pondered the fact without coming to any hard conclusions. In Gershwin's rarefied world, being gay or bisexual was not the big and horrifying deal it was in the general populace. Aaron Copland, David Diamond, Samuel Barber, and many other movers-and-shakers of composerhood were gay, some of them quite openly. It was an arts-saturated environment, and its most celebrated figures seemed to believe they were above convention.

It doesn't matter to me if Gershwin was gay, bisexual or a racehorse (though he was certainly that). But what interests me is the utter fury with which people deny and denounce such "accusations", even if they're stated as mere surmise. I'm apparently attempting to throw mud at an icon, drag him down into the slime.

Hey, wait a minute!

I did a piece on Nietsche not long ago, and the same "accusations" came up in his biographical material, along with that same strident, near-hysterical denial. It's a lie! He had a girl friend in university once and took her to the Philosopher's Ball! The implication is that I'm giving him a black eye just to be spiteful. And, of course, getting my facts wrong. All wrong. This reminds me of that classic Seinfeld episode where, whenever the issue of gayness came up, the mantra was, "Not that there's anything wrong with that." Denial of the denial? Let's begin the beguine.

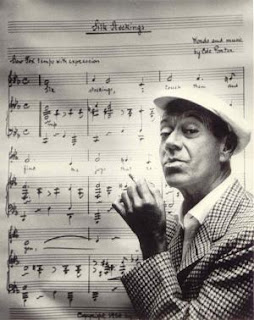

And Cole Porter? Are you kidding? And Noel Coward, let's not forget him. Gay! Gay! Yes, I'm going to ruin their reputations right here and now by saying they loved men (which is obviously a horrific crime - it goes without saying, doesn't it).

Huh??

Come on, people. The suggestion that some great literary or musical figure might have been gay is not automatically slander. In expressing that view, you're revealing a small and very homophobic mind. But your small-mindedness is such that you don't even see it, or at least won't admit it.

"Oh, I knew someone who was gay once and he was a real nice fella." But he's not Gershwin. Or Cole Porter. Or Johnny LaRue.

Imagine these same people were claiming, vehemently and furiously, "he was NOT black!", "he was NOT disabled!', "he did NOT have PTSD!", or any other sensitive categories, and these same people would be horrified. It's OK to be those things now - maybe - supposedly. Or not, but we have to say so, even if we don't believe it. (Though, think about it. A hundred years ago, would it have been acceptable to claim that some important/famous white figure "might have" had black lineage? Think of the outcry, the insistence he was blonde and got a suntan, or something equally ludicrous.)

But why then isn't it OK for Nietsche or Gershwin or any other major figure to be gay or bisexual (bisexual being a category that seems to have been lost in the shuffle, the implication being, for God's sake, make up your mind! Being on the fence like that is oh-so-politically incorrect, even disloyal to the cause.) Sexual orientation still seems to be fraught with confusion. If a man gets married at any time in his life, and (especially) if he fathers a child, he's "not gay". The assumption is, a gay man would not touch his wife with a ten-foot pole. She would remain chaste and pure for 25 years while he pulled out the bodybuilding magazines he kept under his mattress.

People's minds are still in brontosaurus mode. They're stuck, and their thinking is very dusty. Is social change just hurtling along too fast, or what? Is this trapped-in-amber mode of thinking just simple physics: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction?

Whatever. They piss me off! So Gershwin was gay. Or might have been. Does that take away anything at all from his contribution to music? In some distant universe, not this one, we might even see it as a positive attribute, something that adds to the richness and complexity of that extreme rarity, the blazing miracle of creative genius.

BONUS POST. This is the piece I kept finding during my GershQuest of last year.

gramilano

ballet, opera, photography...

Michael Feinstein’s book on the Gershwins called, sensibly, “The Gershwins and Me” (Simon & Schuster) was published in October. While he was still working in piano bars, Feinstein got to know Ira Gershwin intimately, cataloguing his collection of records, unpublished sheet music and rare recordings in the Gershwin home over a period of six years.

The gay or not gay question has floated about George Gershwin even during the more restrained time when he was a young composer. It is an issue Feinstein tackles in his book. America’s National Public Radio asked him about it:

So many speculated that George Gershwin was gay because he never got married. And somebody once said to Oscar Levant, you know, George is bedding all those women because he’s trying to prove he’s a man. And Oscar Levant said: What a wonderful way to prove it. There have always been rumours circulating about George’s sexuality, and I addressed it because so many people have asked me about it, and it’s important to the gay community to identify famous personalities as being gay. In the case of George, it’s all rather mysterious because I never encountered any man who claimed to have a relationship with George, but a lot of innuendo.

Yet Simone Simon said that she thought that Gershwin must be gay because when they were on a trip together, he never laid a hand on her, she said.

Cecelia Ager, who was a very close friend of George’s and whose husband Milton Ager was George’s roommate, once at the dinner said, well, of course, you know, George was gay, and Milton said: Cecilia, how can you say that, how can you say that? And she just looked at him and said: Milton, you don’t know anything. But when I asked her about it, she wouldn’t talk about it. So it still remains a mystery.

My own theory is that I think that the thing that mattered most to George was his music. I think he could have been confused sexually. I don’t know. I think that he had trouble forming a lasting relationship.

Kitty Carlisle talked about how George asked her to marry him, but she said that she knew that he wasn’t deeply in love with her. But she fit the demographic of what his mother felt would be the right woman for him.

This is an extract of NPR’s long talk with Michael Feinstein.

Photo: left to right, George Gershwin, Michael Feinstein, Ira Gershwin

NOTE: here is the Cambridge Dictionary's definition of innuendo:

So many speculated that George Gershwin was gay because he never got married. And somebody once said to Oscar Levant, you know, George is bedding all those women because he’s trying to prove he’s a man. And Oscar Levant said: What a wonderful way to prove it. There have always been rumours circulating about George’s sexuality, and I addressed it because so many people have asked me about it, and it’s important to the gay community to identify famous personalities as being gay. In the case of George, it’s all rather mysterious because I never encountered any man who claimed to have a relationship with George, but a lot of innuendo.

Yet Simone Simon said that she thought that Gershwin must be gay because when they were on a trip together, he never laid a hand on her, she said.

Cecelia Ager, who was a very close friend of George’s and whose husband Milton Ager was George’s roommate, once at the dinner said, well, of course, you know, George was gay, and Milton said: Cecilia, how can you say that, how can you say that? And she just looked at him and said: Milton, you don’t know anything. But when I asked her about it, she wouldn’t talk about it. So it still remains a mystery.

My own theory is that I think that the thing that mattered most to George was his music. I think he could have been confused sexually. I don’t know. I think that he had trouble forming a lasting relationship.

Kitty Carlisle talked about how George asked her to marry him, but she said that she knew that he wasn’t deeply in love with her. But she fit the demographic of what his mother felt would be the right woman for him.

This is an extract of NPR’s long talk with Michael Feinstein.

Photo: left to right, George Gershwin, Michael Feinstein, Ira Gershwin

NOTE: here is the Cambridge Dictionary's definition of innuendo:

(the making of) a remark or remarks that suggest something sexual or something unpleasant but do not refer to it directly: There's always an element of sexual innuendo in our conversations.

Here we touch on the interesting issue of "unpleasant" being juxtaposed with "sexual", which opens up a whole new can of worms: that there's something unsavory and reputation-destroying about sex itself, unless it takes place in the heterosexual/marital bed, infrequently, in the missionary position. And only when you want a kid.

.jpg)

.jpg)